Combat Food Waste With Fermentation

Last October, American food professionals visited fermented food producers to deepen their knowledge of Japanese fermentation culture during the “Hakko Tourism in Japan” tour campaign. As part of the tour, organizers held a tasting session where guests gave candid advice from the perspective of the American market to food product manufacturers looking to enter the United States market.

Our relationship with fermentation

Fermentation today

It is probably safe to say that fermentation as we know it today was born from necessity—a necessity from every scrap of nutrition needing to be secured and amplified. For example, some Japanese tsukemono techniques arose to find uses for the by-products of other food productions.

For instance, nuka-zuke are fermented in rice bran (nuka), a by-product of polishing rice. Interestingly, eating nuka-zuke was shown to reduce the occurrence of beriberi, a disease that comes from vitamin B1 deficiency resulting from the widespread consumption of polished rice.

kasu-zuke are pickles fermented in sake lees (kasu), the mash of rice and yeast that is a by-product of making sake. In a modern twist Ine to Agave Brewery is now redefining what is possible with the sake kasu from their brewing. They are turning it into a delicious vegan mayonnaise—Koji Mayo. This mayonnaise is rich and creamy and doesn’t disappoint the palate.

In Indonesia, okara, the soybean mash left over from making soy milk and tofu, is made into oncom: a tempeh-like bean cake that is delicious, filling, and nutrient-dense. These foods are the original protein rich meat analogs.

Preventing food waste with fermentation

Rediscovering fermentation

Scientists are also looking at fermented avocado seeds for flour in the Middle East and fungus-based fermentation in Colombia. With fermentation, they can turn a current edible waste product that mostly gets tossed out into something that could provide incredible nutrition.

The avocado pit is the most nutrient-dense part of an avocado; 70 percent of its antioxidants are locked up in it. In Eastern Europe, stale rye bread has been used for centuries to make a lightly alcoholic beer called Kvass.

These traditional ferments are no longer relics of the past but are being rediscovered and reimagined.

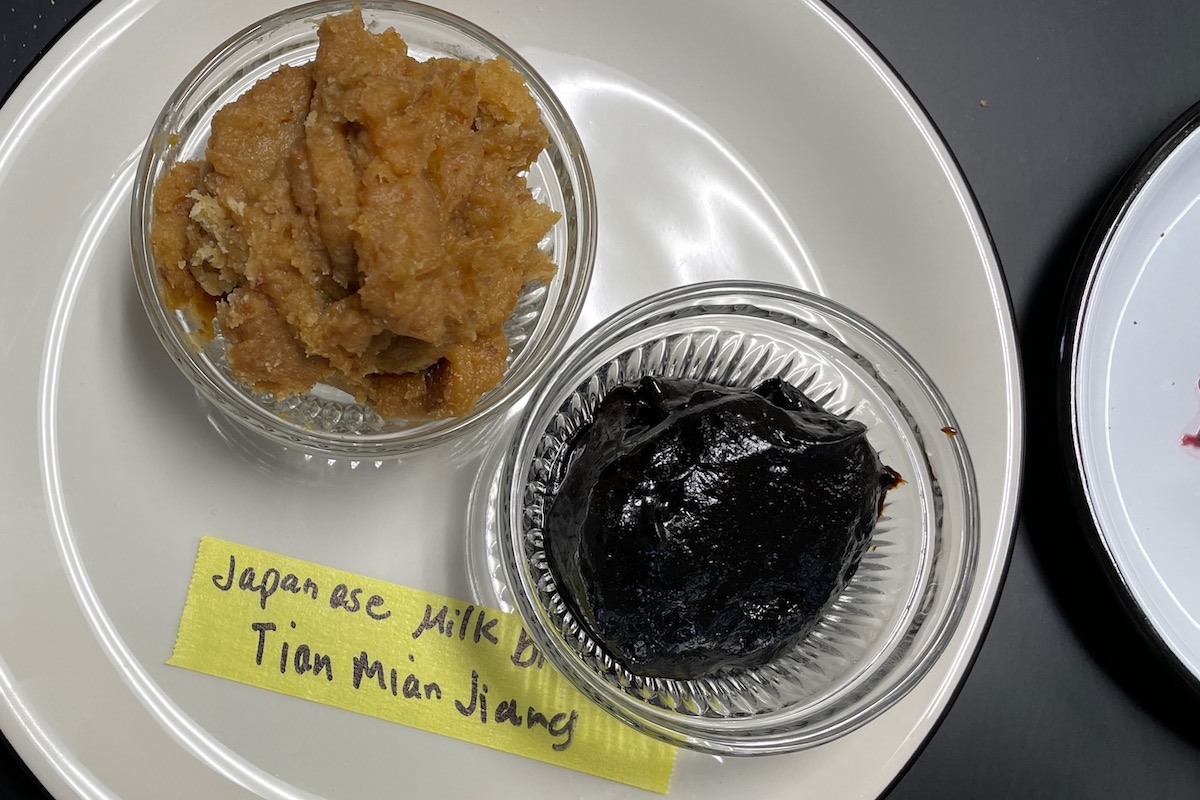

In Boulder, Colorado, Mara Jane King and the team at Dry Storage, a grain mill and bakery, are using their stale bread to make delicious Kvass to serve in their restaurant. Mara is also making enchanting sourdough gochujang and a delectable Japanese milk bread tian mian jiang.

In Chiba City, Chiba Prefecture, Japan, a bakery, Kawashimaya, and a brewery, Makuhari, are collaborating to develop bread beer and other products from unsold bread in their Chiba Upcycling Lab.

Upcycling with fermentation

Bread Miso

(Photo by Kirsten K. Shockey)

Ingredients

- 340 grams bread bits, cut into crouton-sized pieces and toasted to a near char

- 170 grams koji rice

- 2 cups (473 ml) water (boiled and cooled to around 100°F/38°C)

- 61 grams sea salt

- Extra salt for packing in jar

Directions

(Photo by Kirsten K. Shockey)

2. Massage it together and let it sit. It will take some time for the hard toasted bread to hydrate. After an hour or so, massage again. When the mixture feels moist and ingredients are well combined, it is ready to pack into a jar.

3. Using a bit of boiled water, cooled to handle, rinse the inside of your fermentation jar, making sure to coat all of the surfaces. Then sprinkle about 1 tablespoon salt into the jar, coating the vessel’s sides and bottom.

4. Spoon the chickpea mixture into your jar or crock, doing your best to remove as many air bubbles as possible.

5. Set a small piece of unbleached cotton cloth or parchment paper cut to fit the diameter of your vessel on top. Sprinkle about 1⁄2 tablespoon of salt along the edges of this cover to seal any gaps. Weight the miso as best you can with weights or a salt-filled plastic bag.

6. Cover the jar with a cloth, securing it in place with a string. Set it in a cool spot and allow it to ferment. Ferment for 6 months or more, but feel free to taste it much earlier.

(Photo by Kirsten K. Shockey)

7. When you are ready to harvest your miso, open it up. You may need to scrape off the top surface of the miso until you get to something that looks nice and rich in color. You can either strain off the tamari (the liquid pooling on the top of the miso) or you can mix it back into the miso and eat it as is. Your miso may be chunky; if you prefer a smoother paste, process it in a grinder or food processor. Store in an airtight container. The miso will keep indefinitely in the refrigerator.

For Further Reading:

How Fermentation Works to Preserve Food and Punch Up Flavors

Kirsten K Shockey is a renowned fermentation expert, author, and co-founder of The Fermentation School. She empowers people to connect with their food through hands-on workshops and her popular books, including Fermented Vegetables and Homebrewed Vinegar. Her expertise has made her a trusted authority in the world of fermentation.