What is Koji-Kin Doing on Your Rice?

Last October, American food professionals visited fermented food producers to deepen their knowledge of Japanese fermentation culture during the “Hakko Tourism in Japan” tour campaign. As part of the tour, organizers held a tasting session where guests gave candid advice from the perspective of the American market to food product manufacturers looking to enter the United States market.

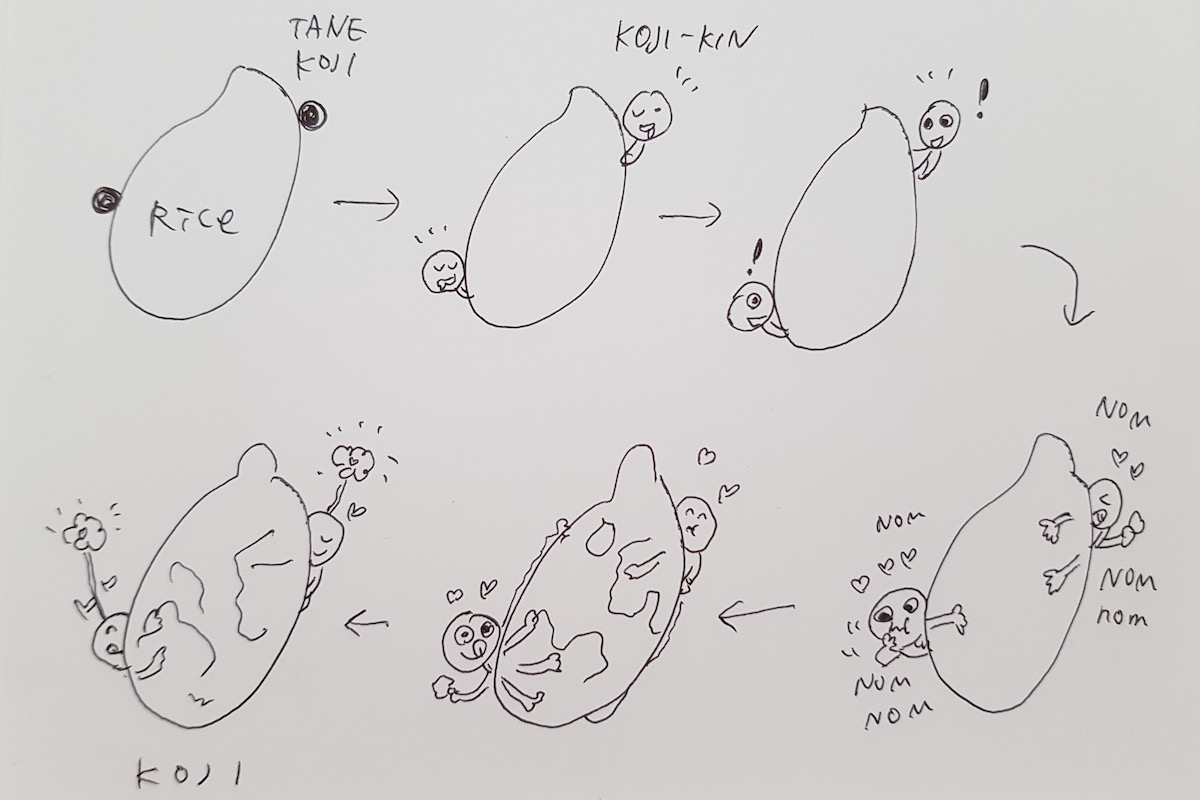

In the previous article, I went through the general growing process of koji. Now I want to illustrate what koji-kin is doing on your rice to transform it into koji rice.

Moisture Levels of Koji Kin

Mycelia seek for moisture. This is a key. Since koji-kin is able to determine what kind enzyme to produce at the moment they wake up on the substrate, you need to make sure where you guide them to grow mycelia towards to. The type of the enzyme you often expect from koji rice is amylase. Amylase is carbohydrate breaking down enzyme. With this enzyme, you are able to make sweet amazake, or sweet miso, or any other application you can utilize the feature of its ability to break down the carbohydrate into a simple sugar monocle. So where can koji-kin produce amylase? That’s where most carbohydrate is, which is inside of the rice grain.

Now remember that mycelia seek moisture. If you let the rice retain enough moisture inside the grain, koji-kin automatically starts growing mycelia towards the centre of the grain.

This is usually the most preferred case of rice koji making. If you are growing koji-kin on soybeans, that’s another story.

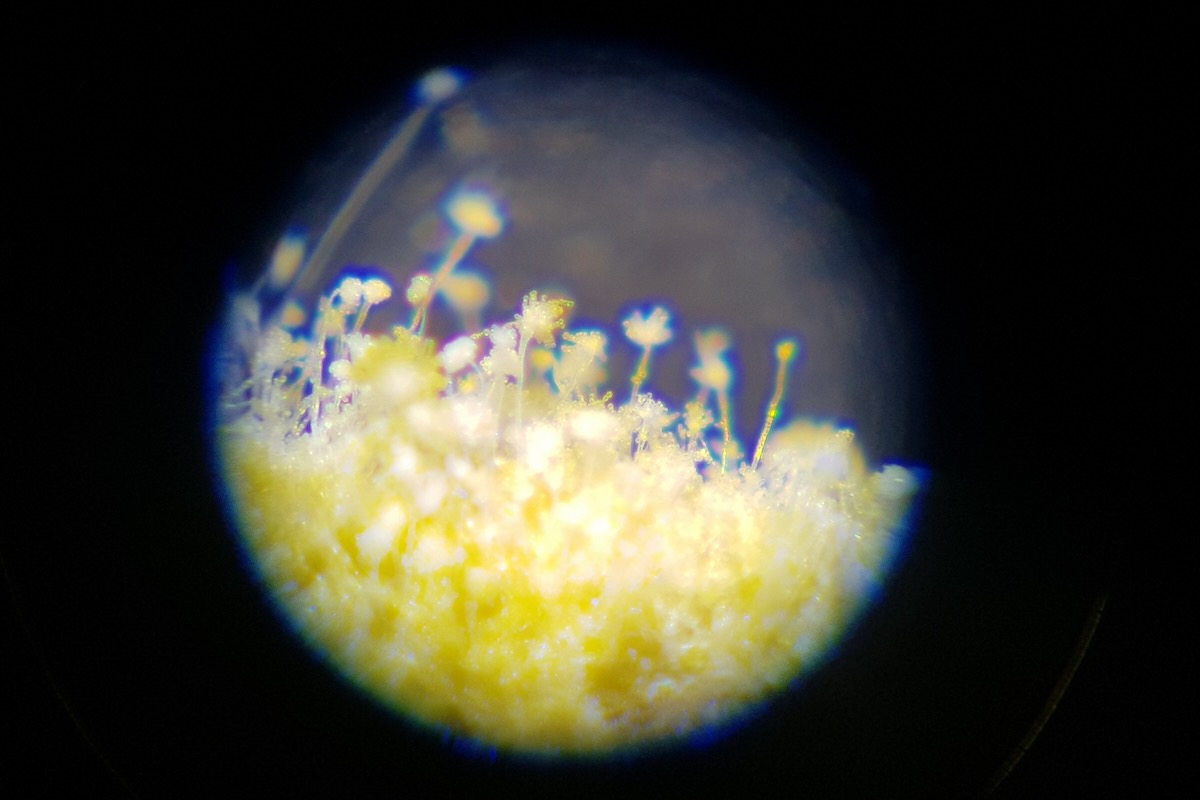

Now, look at the first drawing again. The bottom left is the end of the process. Can you see a little flower blooming on the heads of koji-kin? This in fact carries spores to the next life, because koji-kin finished their one round of life, and are ready to pass it to the next generation. This flower is often what you see as the fluffy top coating of your koji, and depending on how humid you keep the environment/muro, your koji is full of this flower field all over it. There is no definite answer whether you should see this or not, as what you want to care most is whether they grew mycelia inside of the grain or not. As long as that’s done, the flower field is up to your choice.

Marika Groen is the head of Malica Ferments, an online platform dedicated to fermented products. As a Kojiologist, traveler, brewer, photographer, and writer, she published the book "Cosy Koji" in 2021, offering insights into the art of Koji making based on her worldwide lectures and experiences.