Trying Out Different Rice Varieties

Last October, American food professionals visited fermented food producers to deepen their knowledge of Japanese fermentation culture during the “Hakko Tourism in Japan” tour campaign. As part of the tour, organizers held a tasting session where guests gave candid advice from the perspective of the American market to food product manufacturers looking to enter the United States market.

Belated happy New Year to you. How did your 2023 begin? Mine started with koji making and miso preparation for the coming years.

I have recently been experimenting with several varieties of rice and wanted to share my experience with you. Last year, I wrote about “Rice for Koji to Make Sake and Miso”. Today, I want to talk about the size difference mainly.

First, short-grain rice is used for general koji or koji risotto making, although in some Western countries long-grain rice such as Jasmine or Basmati is used. Living in Europe, I often use Koshihikari rice grown in Italy, such as Yumenishiki. The grain is approximately 5 mm long, absorbs water easily and takes about an hour to steam. This year, as that rice was not readily available, I happened to have the opportunity to try a number of different varieties.

One is Utage short-grain rice from Vietnam and the other is Tosya Pirinc, a risotto/paella rice from Italy or Turkey. Other Italian risotto rice of various classes exist, such as Arborio, Carnaroli and Orginario, which can be used to make koji.

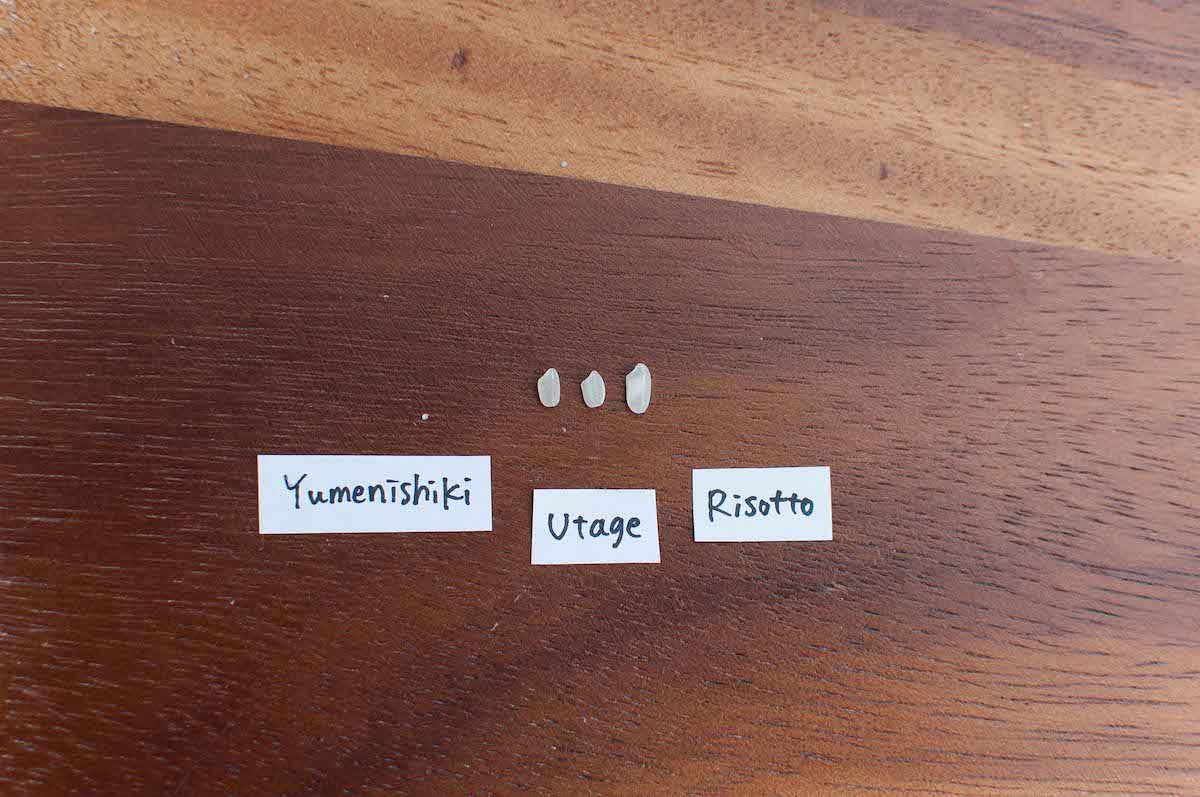

From the left: Yumenishiki, Utage, Tosya Pirinc risotto/paella rice

Rice high in amylopectin is sticky, while rice high in amylose is hard and dry. Usually, the stickier the rice you eat, the better it tastes, which means it needs amylopectin. For example, glutinous rice is mostly made up of amylopectin, which makes it sticky when cooked.

So why not use that delicious glutinous rice to make koji? However, if you try to make koji by steaming polished glutinous rice, the rice grains will not separate from each other because of the stickiness, making it difficult to make koji. This is why ordinary rice with some amylose is suitable for making koji.

Ordinary rice is made up of 70% starch and 20% amylose, which means that it is ideal for making koji because the rice does not stick together as much as glutinous rice.

The next thing to consider is the size of the rice. This time, I compared the rice grains of Yumenishiki, Utage and Tosya Pirinc risotto rice side by side.

One major difference, however, is that when the rice is cooled down to about 40°C after steaming and before inoculating with koji spores, there was a big difference in the way the rice dried out.

Rice with large grains, such as risotto rice, has a high moisture retention rate and does not lose moisture so quickly when spread out immediately after steaming. In contrast, rice with smaller grains, such as Utage, has the problem that if it is spread out and mixed slowly over time to lower the temperature, it dries out relatively quickly in the process of lowering the temperature.

In koji making, once the moisture has been lost from the rice, it cannot be restored. Spraying water is also not a good idea. It only wets the surface but does not penetrate into the rice, and rice that is wet on the outside invites the possibility of bacteria nesting in some cases.

As a solution:

- Do not spread the steamed rice immediately, but leave it wrapped until the temperature drops to a certain extent.

- Lower the temperature of steamed rice in a humid environment.

Moisture is essential for koji germination, so a major key is how much moisture is retained in the rice on the first day.

On the other hand, risotto rice had the advantage that its surface remained relatively unsticky after steaming and was easy to break apart during cooling.

For example, if the grains are small, it simply means that the amount of food eaten by the koji fungus is less, so the koji making time is shorter. On the other hand, risotto rice is large, so if you want the koji fungus to eat up all the nutrients in the rice, you will have to wait longer. If you are in a hurry, you may be able to shorten the koji-making time by using rice with smaller grains.

Another thing to pay attention to is the type of the cloth you use for wrapping the rice after inoculation. If you use small grains, you may want to use thinner cloth, so that the essential moisture wouldn’t be stolen by the cloth. For larger grains, it’s okay to use a thicker cloth, so the cloth would absorb the excess moisture from the rice, preventing over condensation to invite unwanted bacteria for koji making.

Marika Groen is the head of Malica Ferments, an online platform dedicated to fermented products. As a Kojiologist, traveler, brewer, photographer, and writer, she published the book "Cosy Koji" in 2021, offering insights into the art of Koji making based on her worldwide lectures and experiences.